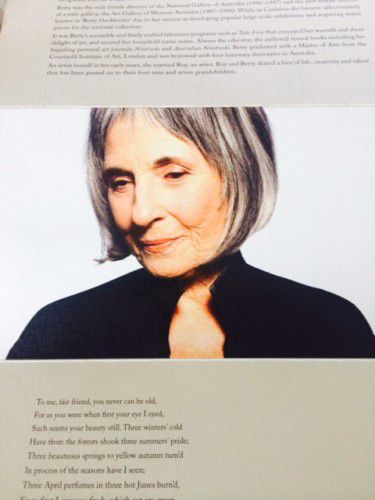

“SHE was one of those people who just lit up a room,” National Gallery of Australia director, Gerard Vaughan told a packed house of friends, admirers and former colleagues of the late Betty Churcher at the Gallery’s Gandel Hall this morning.

The idea of the occasion, Dr Vaughan said, was to pay respect to a much loved and missed personality in the art world, one remembered by many for her “wonderful, cascading laugh.”As he sketched her life, paying particular attention to a childhood in Brisbane where she very nearly missed out on a full secondary education because her father didn’t think it was suitable for a girl, he outlined how Churcher had become a pioneer woman critic, historian, arts administrator personifying “determination, wrapped in charm” and in later years on TV, a household name throughout the country. He drew titters from the audience as he described how the late Prime Minister Gough Whitlam had enticed to Canberra. She in turn had persuaded him to wear a toga on a formal occasion, something he took to very easily.

Former NGA chair Kerry Stokes sent a message to Dr Vaughan describing how the late Mrs Churcher had changed his entire perspective on art collecting

Federal Minister for the Arts, George Brandis thanked her four sons Ben, Paul, Peter and Tim for the invitation extended him to participate in what he called “the celebration of the great Australian story.”Former senior NGA staff are and later director of the Art Gallery of Western Australia, Alan Dodge sketched the difficulties Churcher had encountered when she succeeded founding NGA director James Mollison in 1990. Dodge said that she was considerably aided by knowledge of her own strengths and weaknesses, a sense of humour and the fact that she had within her “a streak of steel.”

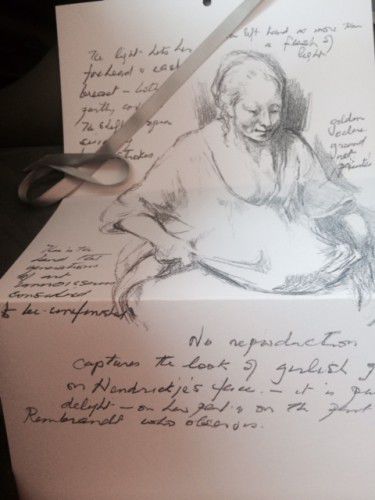

Dodge went on to describe her early espousal of blockbuster exhibitions aimed at bringing the general public into the gallery and gave a sometimes hilarious description of a visit he and Mrs Churcher had paid to Moscow during which she sketched sacred icons with her pen, “she often used. That skill,” he continued.

In a video message from London, retiring director of the British Museum Neil MacGregor said he had first met Churcher during the early 1990s when she and art entrepreneur Bob Edwards, together travelled around and changed the European view of lending to Australian galleries.

“Betty believed that pictures matter” McGregor said as he spoke of her final visit to London in 2006 – “pictures were Betty’s friends.”

In a moving speech, artist John Olsen talked about churches understanding of the artistic process, which he described as “getting into the engine room” of art – “wonderful wonderful wonderful, rare rare rare,” he said. Gifted with an extraordinary ability to communicate, Olsen concluded, “such people don’t die.”

Olsen was followed by Betty’s artist son Peter Churcher, who read a letter from an anonymous member of the public, a section from Deuteronomy, which advises the reader to “choose life” and some words dictated by Betty from her hospital bed in Queanbeyan to his wife, making it clear that just like the rider in one of her own sketches, she was about to disappear over the hill.

Former Australian Gov Gen Quentin Bryce, a Queenslander like Churcher, spoke of Churcher’s early years schooling at Somerville House, where Margaret Olley also studied, giving a unique insight to the social milieu where it had only been possible for Churcher to study overseas by appealing to women donors, including the poet Judith Wright. Once she knew she was to head to London, Dame Quentin said, Churcher’s words were “I am definitely and positively out of here.”

In a speech full of more intimate observations about the late Roy and Betty Churcher as a couple, she depicted Betty as a devoted mother who had given up a potential art career, saying, “I wanted my babies more than anything.”Married to an artist, she had quickly become the main family breadwinner, but as Dame Quentin said, women rarely talked about the “slings and arrows” involved in breaking the glass ceiling in those days”. But as her husband Roy would say, the key was “the driven thing in her nature.” When she came to Canberra, the papers were full of descriptions of her as a middle-aged mother. “What are they expecting, that she would bring a duster?” Dame Quentin asked. Actually she did.

The surprise of the morning came in the form of a letter from former Prime Minister Paul Keating, read by Dr Vaughan. During a period when the Canberra press gallery had written Keating off as a clock collector, he was able to spend time with Churcher, often sitting quietly in front of a painting with a drink . “We shared a unity ticket on one thing,” Mr Keating said that was the need to augment the collection with major international works of art. “We were both shocking quality snobs, but she was a big snob than me,” he said. Although praising her for putting her family first, he argued that she had best served the nation through her work at the head of such an important artistic institution as the NGA.

The whirlwind morning of speeches was accompanied by the screening of family of Churcher family photographs, as well as images from the late Betty Churcher’s own art and career.

UPDATE: Lyn Mills has sent us the group photograph:

The post ‘Determination, wrapped in charm’ – Betty Churcher celebrated appeared first on Canberra CityNews.